Aviation

The history of speed records is littered with many prominent attempts to drive faster, fly distances in shorter times and achieve a ‘first’ as either a driver or a flyer. The excitement and adrenalin rush achieved by these men and women, starting at the beginning of the last century, continues into the 21st Century, with for example Elon Musk and Tesla, but that’s another story!

Let’s examine some of these early successes and what led the pioneers to exceed and excel in their chosen speed attempts and importantly, where these speeds led to and where we are today.

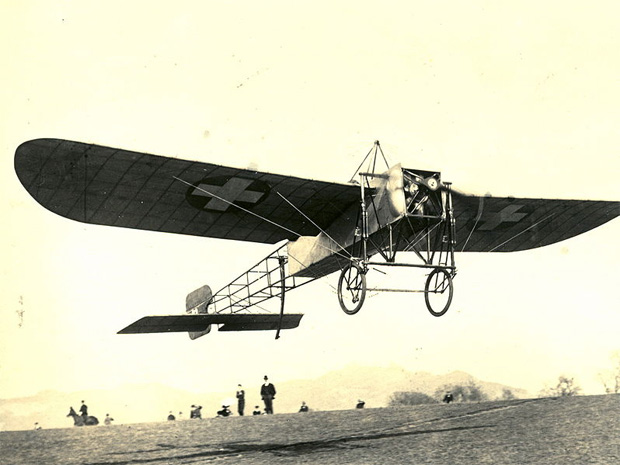

Bleriot’s take off from France in 1909

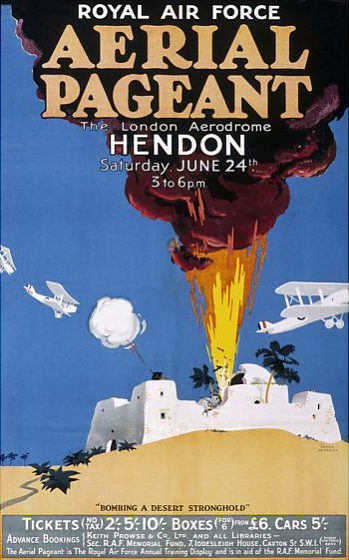

Perhaps the first attempt was Louis Bleriot who, only 6 years after the first ever flight by the Wright Brothers in 1903, flew across the English Channel in 1909. His Bleriot X1 achieved an average speed of just 45 mph at an average height of 250 feet above sea level. Why not visit Hangar 2 at the RAF Museum in Hendon, where you can see an early example of the Bleriot XXV11 monoplane. Just 10 years later in 1919, Alcock and Brown flew across the Atlantic Ocean, in their open cockpit Vickers Vimy, covering a distance of 1,890 miles, at an average speed of just 115 mph. 50 years later, a replica Vimy flown by Steve Fossett, re-enacted the trans-atlantic flight at a similar speed. This aircraft is now displayed at the Brooklands Museum.

Our next ‘leap’ in speed was during the 1930s’, with the London to Australia, MacRobertson sponsored air race, which was won in 1934 by Scott & Black in their twin engine, stress skinned plywood DH88 Comet Racer. Their average speed was 200 mph. It’s definitely worth a visit to see this original aircraft at one of the flying displays later this year. Click here for visitor information for The Shuttleworth Collection.

The DH88 Comet Racer ‘Grosvenor House’ hangered at The Shuttleworth Collection

The Schneider Trophy’s winning S6 seaplane racer in 1931

However, the big step up occurred with the development of the Schneider Trophy S4,S5 and S6 seaplane racers between 1927 and 1931, where the average winning speed increased from 282 mph to 340 mph. The UK having won the trophy on 3 consecutive dates, now resides in the Science Museum in London. The original 1929 S6 seaplane racer, N248 is now on display at the Solent Sky Museum in Southampton – well worth a visit when you’re next down on the south coast!

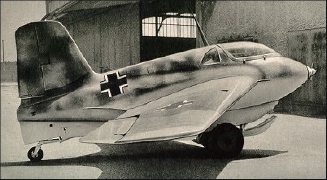

During WW2, respective fighter ‘piston’ aircraft raised the speed threshold from 300 mph upwards, until the advent of the jet fighter in 1944. Whilst the British Gloster Meteor achieved 417 mph, the German Me 163 Komet achieved a breath taking 702 mph also in 1944!

The Me163 Komet jet fighter 1944

After the war, a number of unsuccessful attempts were then made to break the sound barrier of 770 mph. However, it wasn’t until 1947, when Chuck Yeager, a 24-year-old US Air Force test pilot, broke the sound barrier to achieve Mach One! His jet aircraft no less, was the Bell X-1, named ‘Glamorous Glennis’ after his wife. Launched from a Boeing B29 Superfortress at 20,000 feet, Chuck took the aircraft to 42,000 feet before accelerating the X-1 to achieve Mach 1.05 and breaking the sound barrier: creating a sonic ‘boom’ over the Mojave in the US. Yeagar died earlier this year, aged 97 years – click here to read his obituary in The Times.

The Bell X-1, named ‘Glamorous Glennis’

It was his success that led the UK government to set up the Advanced Fighter Project Group in 1948, from which 2 supersonic designs emerged: the Fairey Delta and the English Electric P1, which became the famous 1500 mph ‘Lightning’ jet fighter, entering RAF service in 1960. Barnes Wallis at Brooklands also developed a supersonic design with a revolutionary ‘swing Wing’ and under his direction, research into supersonic aerodynamics that contributed to the design of Concorde.

At about the same time, BAC developed the TSR2, which unfortunately became too expensive and was cancelled in 1965. Yet another jet, the HP115, with a revolutionary ‘Delta wing’ was being developed as a supersonic transport concept. This led to the joint British and French design named Concord or ‘Concorde’ the eventual name used! Concorde entered service in 1973 and flew for 30 years until being grounded in 2003, after the earlier disastrous crash in Paris.

Today, aircraft speeds can be in excess of 2,000 mph, these include the McDonnell Douglas eagle and one of the fastest jet aircraft being the Bell X-2. Its top speed of 3,370 mph, is over 4 times the speed of sound!

Motoring

So, now we’ve read about the history of air speed achievements, what about the ‘drive’ to be faster on four wheels? Funnily enough, the time line for chasing a faster and faster speed record was very similar to that of Aviation. After all the development of the piston engine often led to its development on the road and in the air. For example, Rolls Royce had developed their motor engines, installed in their early cars and of course the development of their ‘R’ aero engine, was installed in the S6 seaplane racer mentioned earlier and later became the world-famous merlin engine installed in the Supermarine Spitfire.

We’ll start with the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run, the first 60 mile race being in 1927, with an average speed of not more than 20 mph.

Cars leaving London on the annual London to Brighton Vintage Car Race

However, the advent of motor racing in the 1920s’ led to a substantial increase in driving speeds and the development of a purpose-built racing track at Brooklands, at Weybridge in Surrey. Click here to find out more about the race track at the Brooklands Museum.

It was here that the legendary Sir Malcolm Campbell broke 9 land speed records between 1924 (146mph) and 1935, when he became the first man to break the 300 mph barrier in his racing car ‘Bluebird’. Alongside Sir Malcolm was another daredevil driver, namely Sir Henry Seagrave, who set 3 land speed records, in 1926 (174 mph), 1927 (203 mph) and 1929 (231 mph). Another racing rival was George Eyston, who broke the land speed record 3 times between 1937 and 1939.

His fastest time was 357 mph in 1939 in his famous ‘Thunderbolt’ car raced at Utah, Arizona.

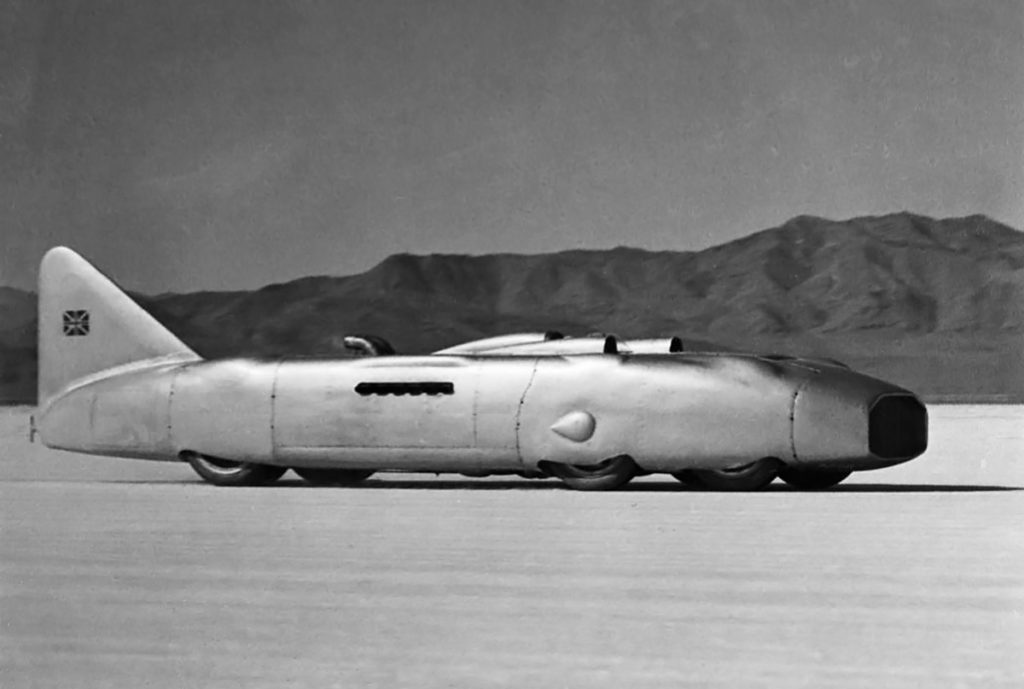

Yet the stakes were still rising and in 1939, John Cobb set a new land speed record of 367 mph in his Railton Special at Bonneville Salt Flats, increasing it to 394 mph in 1947. The Railton Special had an aero engine fitted and is still driven regularly at Brooklands Museum.

The Railton Special on a recent airing at the Brooklands racing

The thirst for speed continued with the installation of the jet engine in place of the combustion engine, fitted in boats and cars, which combined with streamlining their respective bodies enabled a step change in setting faster water and land speed records.

Many of the early motor racing drivers had taken on breaking the water speed record, including Henry Seagrave and Malcolm Campbell, mentioned above.

However, it was Donald Campbell, son of Malcolm, who carried on the ‘Bluebird Dynasty’ by breaking 8 world speed records in the 1950s’ and 1960s’ and became the only person to hold the world land speed and water speed records simultaneously in 1964.

Donald Campbell at Lake Dumbleyung, in Western Australia in 1964 with his 276 mph record breaking Bluebird

However, his luck ran out on January 4th 1967, when Bluebird flipped on Lake Coniston at just over 300 mph and he was tragically killed.

The land speed record was raised again between 1983 and 1997 by Richard Noble, who drove his ‘Thrust 2’ jet powered car to achieve 633 mph.

Richard then became the land speed record project manager to his successor, Andy Green, when the young RAF pilot achieved a new land speed record and broke the sound barrier at 763 mph in his Thrust SSC on October 15th 1997, at Black Rock desert in Utah.

So, Andy Green’s land speed record currently stands. However, he is planning to attempt to achieve 1,000 mph in a new design, named Bloodhound. This car has clocked 628 mph in trials in 2019 while powered by a jet engine. With the addition of a rocket, the vehicle should easily beat the existing world record of 763 mph.

Bloodhound driven by Andy Green

So, to conclude this article, it’s amazing to think that in a little over 100 years of the development of speed on the ground, we’ve gone from 20 mph to 763 mph, whilst in the air, we’ve gone from 45 mph to 3,370 mph and broken the sound barrier with both modes of transport!

Places to visit:

RAF Museum, Hendon

www.rafmuseum.org.uk

Brooklands Museum, Weybridge

www.brooklandsmuseum.com

The Shuttleworth Collection, Biggleswade

www.shuttleworth.org/the-collection

Science Museum, London

www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

Solent Sky Museum, Southampton

www.solentsky.org

RAF Museum, Hendon

Website: www.rafmuseum.org.uk

Brooklands Museum

Website: www.brooklandsmuseum.com

Science Museum

Website: www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

Solent Sky Museum

Website: www.solentsky.org

The Shuttleworth Collection

Website: www.shuttleworth.org/the-collection